MICRO ENGINEERS

May 31, 2020

NEO FRUIT 2.0 FRUIT OF THE FUTURE

June 3, 2020Cities are an important issue in trend studies and forecasting because it will be synonymous of “home” for most human beings. If you want to understand the future of humanity, you will probably have to look for answers in urban spaces very often. So, once we have decided to move from natural landscapes to cement and square blocks, it is worthy to understand it deeply.

Living in the city brought discussions such as public x private, spaces of work x leisure, individual x collective dynamics, or even heritage x development. In this article we approach my research on this topic involving Lisbon, graffiti and Gentrification. In 2018 I visited the zone of Mouraria 9 times, catalogued 39 out of 79 pictures, made two interviews with local artists, attended events and enjoyed traditional bars owned by very sympathetic people. The urbanization of this area recalls economic development besides cultural and social risks, what can contribute to an internationally famous scenario: inequality.

But before we start… why graffiti?!

Have you ever gone on a coolhunt (a hunt where you go out looking for interesting and cool things around the city)? If yes, you probably understood that it becomes easier and more interesting if we are surrounded by innovative urban spaces such as Berlin, New York, London or Tokyo, for example. And to deliver qualified trendspotting you must activate your sensibility for small, alternative and provocative signs stamped in those places. Looking for graffiti (tags, stencils, posters, stickers or murals) is a nice tip to hear local demands, alternative necessities, disruptive art expressions and underground tribes.

According to the two artists interviewed, Street Art means the imposition of a public dialogue. It means screaming for belonging in the public face of the wall — the inside face of the city walls would be its private dimension. Cauê Maia (Coletivo Transverso) says “To call attention to forgotten spaces is part of the language of urban intervention. Those are places traditionally appropriated by graffiti and other technics”. In the end, graffiti represents a manifestation (sign) of social struggle in some contexts, like Lisbon and Amsterdam where the housing situations are critical.

In this way, graffiti can be a tool to understand mentalities and realities that you would not even see through an outsider eye. So, once you are innovating or communicating in an urban space, you should train yourself to be aware and investigative about these graphic cool tracks!

Case Study

Our case shows the public strategy for revitalization of the Lisbon’s zone called: Mouraria. In sum, this very central neighborhood had historically belonged to foreigners (Moorish people), but after the earthquake followed by wildfire in 1755 it was shared with Portuguese people, Fado and sardines. Many years have passed, and this heritage became the recent reality where lifelong housing contracts kept elders other whole families living in the zone, but in terrible conditions.

Camilla Watson’s (#3) work is based on pictures of local people and famous artists of the Portuguese culture. She printed black and white photos on the walls of Mouraria and Alfama because she desired to protect the memory and the soul of these traditional zones through the local people’s faces.

Facing very low rents and higher housing taxes every time, landlords decided to abandon the buildings with the families inside. This situation resulted in the degradation of the urban scenario, the local cultures and the (basic) quality of life. To change this situation, in 2013 a public initiative called “Ai Mouraria” checked houses and buildings and imposed deadlines for the restoration of them. If not, they would have to be evacuated and sold for private interests (AirBnbs and hostels) in name of richer people (France, China, England, Netherlands…).

Since then, good and bad changes have built a gentrified landscape. On the one hand, more public light, better organized car traffic, safer pedestrian circulation, beautifully restored architecture, lots of tourists (9 times the number of local people) and hipster shops with green and conscious products — which local people will never afford. On the other hand, local people were expelled and had to move to far suburbs, the Portuguese language was almost extinct from the routine, and the neighborhood landscape became an unfair visual contrast between building facades.

To confirm and illustrate those dynamics, the following graffiti will approach some main topics: gentrification, economy, cultures and social action. But pay attention to something very special that is hidden in all of that: more than making you an expert in Lisbon, this research aims to show you an applicable model of collecting data, framing it, connecting dots and providing insights in the end.

Gentrification

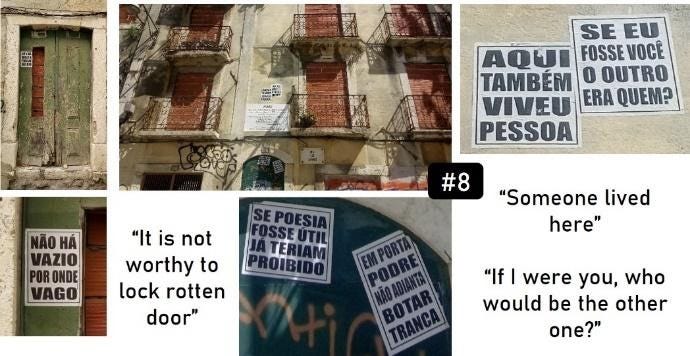

A few graffiti (#6, #7) directly approached gentrification associating it to negative meanings in walls of new/restored building. The feeling of abandonment was expressed through messages like “Late” and “rotted doors” (#8, #9), and can be associated with the emptiness of old buildings, the lack of hope, the good times that have gone. Tracks of occupations (#10) were also found along with projects focused in supporting local people against evacuation.

Economy

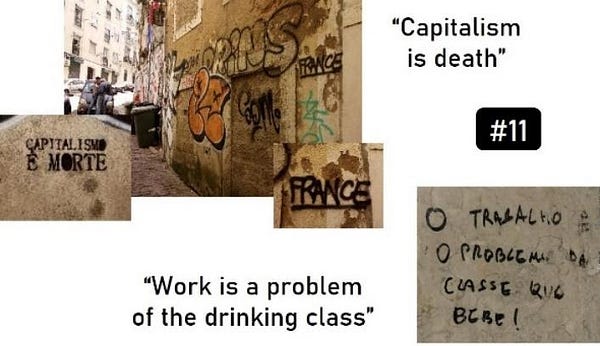

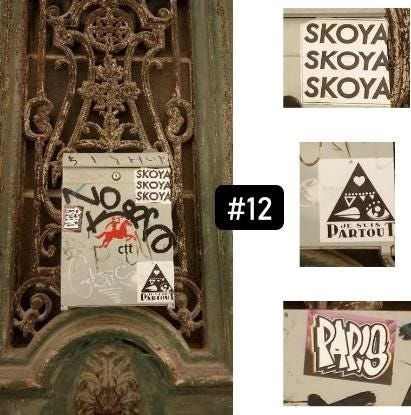

A few mentions about capitalism and working class were collected, but it surprisingly came along with an association with France (#11). This track confirmed the real situation of a massive presence of French people in the zone living, renting and owning shops — 29% of the investments in Real Estate in Portugal come from France. French artists left their marks concentrated, possibly indicating bonding and community. Many of them are famous, like Je Suis Partout and Skoya Assémat-Tessandier — who lives in Lisbon and owns The Switch Gallery in a neighbor zone called Arroios. As one of the artists interviewed quoted, the artists that dialog in the zone “are willing to speak something and can invest on it. They try to disobey. (…) Art is expensive, is for rich people.”. So… are they publicly screaming for themselves or in name of other classes? Are these other classes voiceless or only without conditions to mark the city walls?

Cultures

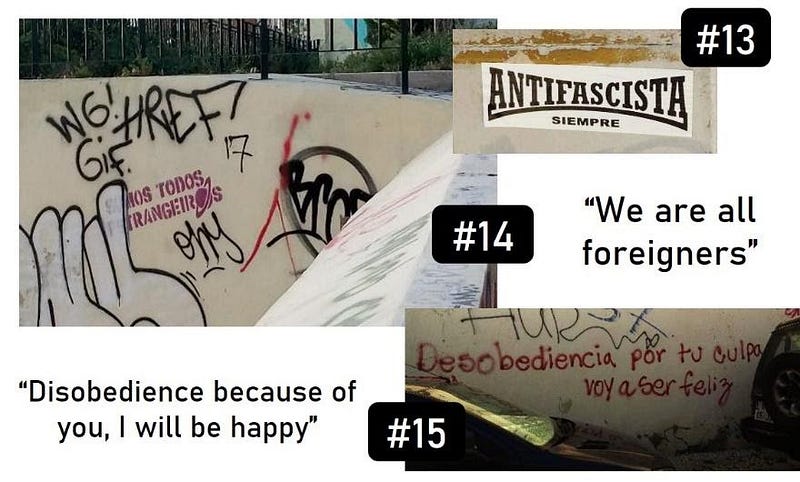

Finding graffiti written in Spanish, French and English was something frequent and symbolic. Lisbon does not only face foreigners as tourists, but also as immigrants. Since the beginning of its history, the city was a multicultural place with strong Maritimes ventures and disputes of territories. Nowadays, these communities are demanding inclusion, visibility and representation.

Social Action / Movements

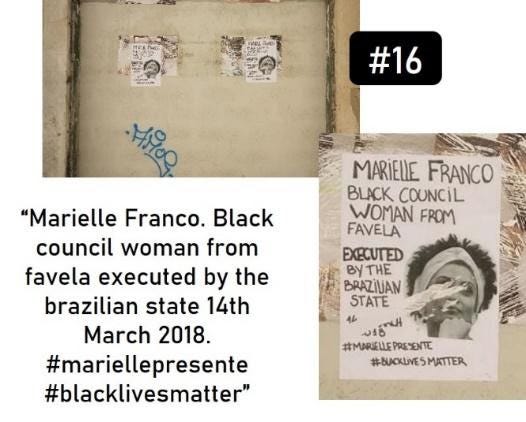

The graffiti not only demand intervention in the current situation, but also gives instructions and tools to act. Squatting, protests and community actions can be found in posters like those #16 and #17. Behind these signs you can see/read/interpret bigger topics such as sustainability, politics, representation, leadership and shared identities.

To conclude this article, we can sum up the strength and relevance of this visual, interesting and political urban sign with a quote from one of the local artists, Cauê Maia (Coletivo Transverso): “The street is the main place of political expression. In the streets you find conflicting voices and inevitably live together with the difference. To act publicly is to suppose the other’s existence, is to instigate the other’s affections. The literature on the walls is placed of the public space, dialogues and disputes space with Publicity, with traffic signs and all the visual pollution of the city. It is an urban poetic game where the attention of the pedestrians becomes an element of dispute.”

References

- BECKER, Howard S. Outsiders: Studies in the sociology of deviance. New York: The Free Press of Glencoe, 1963.

- Deloitte Insights — Inclusive Smart Cities

- HEBDIGE, Dick. Subculture: The Meaning of style. Londres: Routledge, 1979.

- MILES, Malcom. Art Space and the City: Public art and urban futures. Londres: Routledge, 1997.

- PALLAMIN, Vera M. Arte Urbana. 1ª edição. São Paulo: Annablume Editora, 2000.

- Science of the Time — Future of work and urbanities

- Trends Observer — Experienced Narratives, Urbanity

Images Sources

#1 Aka Corelone

#2 Personal achive — Coolhunting in Mouraria, Lisbon

#3 Camilla Watson, Senhor Joaquim.

#4 Rua da Madalena, field research, personal archive

#5 Rua do Benformoso, 278 (Largo do Intendente), field research, personal archive

#6 Rua dos Lagares (Largo das Olarias), field research, personal archive

#7 Rua do Benformoso, field research, personal archive

#8 Coletivo Transverso — Rua dos Lagares (Largo das Olarias), field research, personal archive

#9 Largo do Terreirinho, field research, personal archive

#10 Anomalia, personal archive

#11 Rua da Amendoeira (close to Calçada Santo André), field research, personal archive

#12 Largo do Terreirinho, field research, personal archive

#13 Costas do Castelo, field research, personal archive

#14 Miradouro do Torel, field research, personal archive

#15 Rua dos Lagares (Largo das Olarias), field research, personal archive

#16 Rua do Benformoso, 278 (Largo do Intendente), field research, personal archive

#17 Praça Martim Moniz, field research, personal archive