Climate Change In The Age Of Post-Drought

November 22, 2019Embracing The Power of a Modern Family

December 5, 2019

The nitrogen crisis kills people. But also jobs. The Netherlands are in the frontline

Why Hell Broke Loose Amongst the Good People of Holland

The first of October 2019 farmers from all over the Netherlands drove their tractors to the Malieveld, a park in the middle of the city of The Hague, close to the Dutch Parliament. On their way to The Hague, farmer’s tractors also blocked all the Dutch highways and changing the country in one full-blown traffic jam. Upon arrival the farmers performed the same acts of chaos in The Hague itself. The protests continued over the full month of October, spreading over the whole nation, including the capitals of all Holland’s twelve provinces. The farmers are fiercely fighting for their way of living and their businesses. They demand less firm legislation regarding the allowed amounts of nitrogen emissions in the air, in order to enable them continuing farming.

At the end of October, continuing in November, the building construction sector did the same as the farmers before: paralysing the country with their protests at the Malieveld in The Hague and blocking all of Holland’s main roads with their equipment vehicles, which are in power, quantities and grandeur equal to the farmer’s trucks one month before. Also now the same demand: relaxation of the strict amounts of nitrogen the industry is allowed to disseminate in the air. Building construction comes with considerable nitrogen emissions. The new restrictions on these emissions makes their work impossible, they claim. On top of that there are businesses close to dying as the government not only blocked permissions for new building projects but also for already started ones.

The problem: Biodiversity dies in the Netherlands

Orchids, mosses, lichen, heather, snails, insects, lizards, butterflies, bees, hawks, tits, oaks,… are disappearing in the Netherlands, due to an excess of nitrogen oxide emissions. Nitrogen oxides play a significant role in air pollution and biodiversity loss. They also have a stronger greenhouse gas effect than (better-known) CO2. These emissions are the major threat of nature in the Netherlands. According to the Dutch NGO Natuurmonumenten (Nature’s Monuments) the country only has 15% left of its original biodiversity (since the Industrial Revolution). That’s far less than the rest of Europe (40%) and the rest of the world (70%). More than one third of all species that exist in the Netherlands, are now on the Red list of threatened species. Nevertheless, nitrogen emissions from the Netherlands are still among the highest in the world and the region, once again according to Natuurmonumenten (2019). The Nitrogen Crisis will hit more regions of our planet, but it forcefully reveals itself first in the super-dense and agricultural-intensive Netherlands.

The Benign Beginning: the Sane Nitrogen Cycle

Nitrogen is 78% part of the air we breathe. This atmospheric nitrogen (N2) is ‘assembled’ together in an extremely tight bond that makes it impossible to be absorbed by plants. Atmospheric nitrogen doesn’t interact with any other chemical element. It is simply too stable for that. In nature, there exists some exceptions to this rule though. Some micro-organisms and also (super high voltage) lighting are able to extract this stable N2 from the air and break it down. Then bacteria in the soil can process atmospheric nitrogen into ammonia, which plants need to grow. The plants themselves form/create/build/construct all sort of elements with this reactive N, the most important of them: protein. Animals then eat the plants, and via their excrements let N return to the soil. Once there, bacteria help the excrements returning to nitrogen gas, this way giving it back to the atmosphere. From where plants can use this nitrogen a new when circumstances allow. This is called the Nitrogen Cycle, so beneficial to mankind as it offers us protein and many other essentials. Some of the nitrogen is trapped in plant residues and remains in the soil. With deep pressure and a mighty long time this transfers into fossil fuels. Mind you, up to this point, the Nitrogen Circle can do without any human industrial activity. It is a stable and crucial part of Earth’s System.

Then the Industrial Revolutions came

Plant-available nitrogen is scarce. For most of agriculture’s 10,000-year-old history, the main challenge was figuring out how to cycle usable nitrogen back into the soil. Farmers knew that composting crop waste, animal manure, and even human waste led to better harvests. (Philpott, 2013) Before the scale up of agriculture, hunger was part of the daily lives of people all over the world. Feeding the population was the top-priority of politics.

Around World War I science seriously entered the scene, putting a lot of efforts to extract nitrogen from air. The main ambition was to use it for the military production of explosives. But it worked out on improving agricultural harvesting as well. In 1909, a German chemist named Fritz Haber developed a high-temperature, energy-intensive process to synthesise plant-available nitrogen from air (it’s called nitrate, but we’ll leave the chemical finetuning out of this blog. Here you’ll find more in depth information) Since then humans were able to pull nitrogen from the air and transform it into something that plants could use and prosper on. Agriculture’s millennia-old nitrogen-cycling problem was solved — thanks to science and industry. This cheap and easily produced nitrate has proven to be a blessing as it has managed to scale up food production worldwide and feed many more people. The very best solution to fight hunger was discovered. Today’s industrial-scale farms would not be possible without it. (Philpott, 2013) And, mind you, fighting hunger, empowering to feed the world’s population — increasing towards 10 billion in the year 2100 — is one of the 17 Global Sustainability Goals, formulated by the United Nations. Everybody with a full stomach on this planet basically should realize, that we are talking of a worldwide blessing here: the creation of artificial nitrogen fertilisers.

The Blessing Turns Dangerous

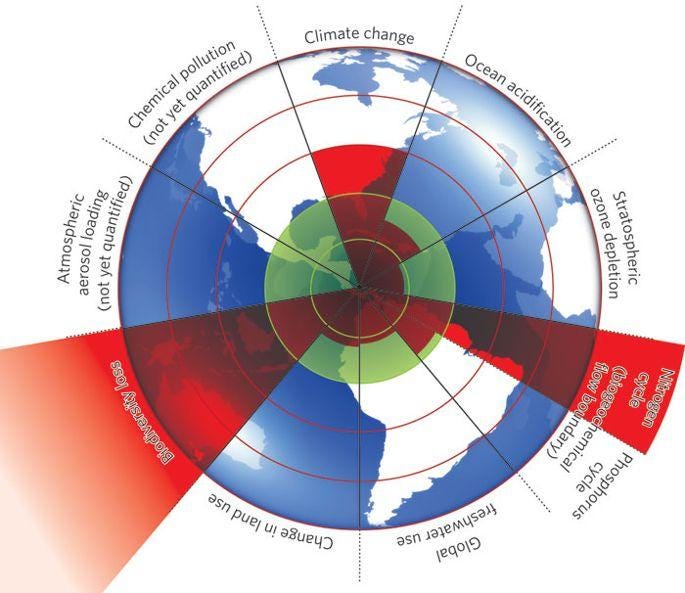

In 2010 Prof Rockstrom gave a TedTalk “Let the environment guide our development: The planetary Boundaries of our finite Earth.” Rockstrom documented that humans are putting a quadruple squeeze on Earth. The first squeeze is population growth. The second is climate change. The third squeeze is ecosystem decline and the fourth squeeze is that our planet does not behave linearly, but non-linearly, that means fully unpredictably when some crucial tipping points have reached and crossed over. All four squeezes are interconnected with each other and react on each other. We’d better stay away from those tipping points.

Stockholm Resilience Centre has identified nine natural systems on earth that regulate and buffer the capacity of our planet’s resilience. (Rockstrom, 2015) Right now we are approaching tipping points that will endanger three of these natural systems. Climate change is one huge threat. Declining biodiversity is identified as another. The third pulsating threat is: nitrogen pollution. If we go further down these paths, we run the utterly dangerous risk that we will enter the next phase of human existence on our planet; from a safe and stabile Holocene towards an unpredictable Anthropocene. And the nitrogen crisis plays a key role in it all. Not only regarding the four squeezes mentioned above, but also when it comes to the breakdown of earth’s natural resilience systems.

Back to the Netherlands

The Netherlands is a little, densely populated, country. With lots of traffic (fossil fuel), lots of industry (fossil fuel) and a huge agricultural sector (fossil fuel, fertiliser and livestock). Actually it is the second largest agricultural exporter worldwide, after the US. In May this year the Council of State, Holland’s top court, ruled that the Dutch rules for granting building and farming permits breached EU law on protecting nature from nitrogen oxide emissions. Prompting a halt to thousands of projects including new roads, housing blocks and airports. This is when all hell broke loose.

Economically speaking there is a lot at stake. The reaction from the Dutch Farmers Organization (LTO) is proportionally fierce: “Must nature be all demanding what we are able to do in the Netherlands? Is it necessary to keep all the nature we have, or could we also say, for these particular species there is no space anymore?” The LTO president speaks out loud and clear on the subject as well: “We are in the Netherlands with 17 million people. But our system is so fundamentally rigid that we are no longer allowed to emit any nitrogen if one finds a plant or animal somewhere that can have very little of it. If we stick to this regime, we are no longer allowed to build houses, we have to drive 70 km/h on the highway and Amsterdam airport Schiphol can halve. I’m against that.”

The good people of the Netherlands — and I am happily one of them — are confronted with what can be called a wicked problem. Can we provocatively also call it: The People versus the Climate? Many Dutch are convinced of the necessity of pro-environmental measures. But when they damage our cherished economy…

Fortunately, the Dutch have a streak of pragmatism running through their collective veins. And even more fortunately, there is another phenomenon that emits lots of nitrogen into the air: speedy cars, allowed to drive 130 kilometres/h (81mph) on our main roads. Lowering their speed would be a possible measure to decrease nitrogen emission and saving the farming and construction building industry. On the 13th of November 2019 our Dutch prime minister Mark Rutte announced that, amongst other measures, we are going to do exactly that. The daytime speed on the Dutch main road will be cut from 130 kilometres to 100 (from 81 mph to 62mph) in a bid to tackle the nitrogen oxide pollution crises. Prime Minister Mark Rutte was far from happy with it. He called it a “rotten measure” — but fully necessary. “No-one likes this,” Mr Rutte told a news conference. “But there’s really something bigger at stake. We have to stop the Netherlands from coming to a halt and jobs being lost unnecessarily.” The existing limit of up to 130km/h will still be permitted at night.

“I’m incredibly disappointed, it’s terrible. But otherwise people would have lost their jobs by Christmas. And I would not have been able to look at myself in the mirror.”

Happy End?

In the Netherlands many appreciate the political courage and long-term view of Mark Rutte. May we call it: vision — or the beginning of a vision? Many others though simply hate the fact that politics have grabbed their freedom to drive fast. In the polls Mark Rutte’s liberal party appears to have lost about one fifth of its seats in Parliament when we would have elections right now.

So, problem solved? Don’t think so. Thanks to the density of its population and the magnitude of its agricultural and construction building industry, the nitrogen crises has blossomed to the full in the Netherlands first. It is a hugely complicated wicked problem. Wicked problems don’t bow their heads politely while they are heading to the exit. On the opposite: More of them to come, also in theatres close to you.

This is a story of the Futurist Club

by Science of the Time

Written by: Linda Hofman

Linda Hofman (MA. Bsc.) is professor in future foods & agriculture, in broader regions of Sustainability and Quality of Life. I help students and organisations to develop, describe and design sustainable futures and develop first steps towards this desired future. For the Future of Food, I consider the whole food systems as my playfield: food from ground to mouth and in all levels from the agricultural sector, food production and technology, but also food and the human body or vice versa.

Currently I am –as one of the founders of the used methodology ‘prototyping for a sustainable future with values’- working on the Sustainable Future of Europe in an International Erasmus project called ‘Foresight’. Also I’m part of a futures study about digital learning environment ‘Learning ecologies’ together with several Dutch Universities and organisations.

I like to give keynotes and was invited at Jonnie Boer’s Chef’s revolution, Paaspop Academy and several food transition tables.

I’m obsessed by the topic future consciousness in correlation with defence modus and like the word ‘meliorist’ and to wear big outdoor boots.